Lancashire's oldest and most dangerous highway

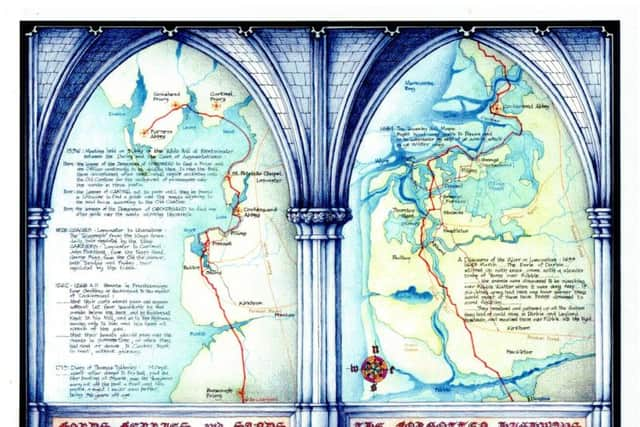

Few people in Lancashire now realise that the A6/M6 corridor is not the only route which traverses the County from end to end and that from earliest times a little known north-south route has existed on the Lancashire coast, by-passing all the main centres of authority and control by fording estuaries and running across the wastes of mosses and dangerous tidal sands.

Starting at the Mersey it crossed the Ribble at Freckleton, the Wyre at Shard near Poulton, the Cocker at Pilling, the Lune at Sunderland point, and Morecambe Bay in two long stretches across the sands, continuing on into Cumbria across the Duddon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is likely that much of the route was already in use in pre-Roman times despite the possibility of higher sea levels, and the siting of the Roman fort at Kirkham makes good practical sense if it was intended to control the connection between the ford at Freckleton on the Ribble and the one on the Wyre at Shard, paved by Romans in 80 AD.

Certainly the next link in the chain, the secret split log pathway across the morass of Pilling Moss, known as Kate’s Pad, connecting the ford at Shard with the crossing of the estuary of the Cocker at Pilling, is of pre-Roman date.

This section fell out of use in later times, probably because it was only suitable for light pedestrian traffic. It was replaced by a route along from Pilling to Preesall and then inland to Shard. One variation of this route is confirmed in a Charter given by Geoffrey de Hackensall to the monks of Cockersand in the 1260s:

‘Moreover, he confirmed to the said Abbot and convent, that when they had desire or need to do so, their carts should pass and repass without let from henceforth by the sands below the bank, and by Hackensall Knott to his mill, and so to the highway, saving only to him and his heirs all wreck of the sea.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe last stage of this route, the connection to the highway, is still called Monks Lane to this day. Another variation shown on the Towneley Hall Maps of 1684 indicates the route actually passed through Preesall and Stalmine via the crossroads known as Preesall Park, described thus:

‘Right hand way goeth to Preesa and so to Lancaster by way of ye sands, which is ye winter way.’ The summer way would be across Pilling Moss.

The whole extent of the old highway probably only began to be fully used in the middle ages with the establishment of the monasteries and their extensive and widely separated landholdings which necessitated travel between the mother houses and their outlying granges which could be many miles away, for example Furness Abbey held land in Stalmine.

The monasteries were also centres of refuge and hospitality for other travellers who would be using the same routes as the monks, and so the Monasteries became responsible for the safe passage of all travellers across potentially dangerous areas such as estuaries and tidal sands.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is confirmed by the attempts made by the government to pass on these responsibilities to the purchasers of monastic lands when the monasteries were suppressed by King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

To address this problem a meeting was held in the White Hall at Westminster in July 1536 between representatives of the Duchy of Lancaster and the Court of Augmentations.

Among items discussed and agreed were the following: Item: The lessee of the demesnes of Conishead to find a Friar and one Officer continuously to be abiding there, to ring the Bell there accustomed when need shall require according unto the old custom for the safeguard of passengers over the sands in those parts.

Item: The leases of Cartmel not to pass until they be bound in likewise to find a guide over the sands adjoining to the said house according to the old custom.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdItem: The lessees of the Demesnes of Cockersand to find one other guide over the sands adjoining thereunto.

There seems to have been some reluctance on the part of the purchasers to undertake these responsibilities and eventually the Duchy agreed to take on the Conishead and Cartmell sections, which is why the Queen’s Guide to the Sands still performs that function in the 21st century.

Cockersand was dissolved somewhat later than the others and the responsibility for that section was allowed to lapse although its local use continued for centuries, as evidenced by the depositions made by Pilling folk in 1808 in defence of their ancient right to take building stone from Wet Arse Scar, an outcrop situated half a mile offshore from the Abbey, and cart it back across the sands to Pilling where it was used in the construction of many buildings still existing today.

Many people testified, including James Bourne of Pilling, ‘aged 88 and upwards’ who said that ‘..when he was about 11 years of age... he drove a cart for one Fazacherley, and he led stone there from under Cockersand Abbey, and stone was led from thence by any person who chose to cart them. He believed that the Pilling people always had a right to get stone from Wet Arse Scare.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe right presumably originated when the whole ‘Hay of Pilling’ belonged to the Abbey, and apparently continued into the 19th century.

During the civil war in the 17th century the route to the south across the fords at Shard and Freckleton saw considerable action. In 1643 a Spanish ship with a lost and starving crew was beached in the Wyre and seized for Parliament whereupon the Earl of Derby ‘stirred up with envie came with a slender troupe of horse over Ribble...’

A parliamentary force under Major Sparrow marched from Preston to Poulton but then had to cross the Wyre at Shard to escape the Earl’s cavalry.

Shard remained an essential link between Over Wyre and the Fylde and on September 14, 1715 Thomas Tyldesley wrote in his diary ‘...went after dinner to Fox Hall, paid 6d. for boating at Sharde, saw the ferryman carry out of the boat a Scot and his packe, a sight I never saw before, being 56 years of age.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUse of all parts of the old highway continued into the 19th century and from 1781, the sands of Morecambe Bay became established routes for coaches and carriers to and from Lancaster, as described in Pigot and Co.’s Directory of 1828-9.

COACHES: To Ulverstone, The Telegraph, from the King’s Arms, daily, hour regulated by the tide.

CARRIERS: To Cartmell, John Pickthall, from the Nag’s Head, Church Street, & George Rigg, from the Old Sir Simon, Market Street, both on Tuesday and Friday, hour regulated by the tides.

To Ulverstone, Geo. Rigg, from the Old Sir Simon, Tuesdays and Fridays, and Wm. Poole, & Sarah Butler, from the White Lion, Penny street, every Monday and Thursday, as tide permits.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, crossing the sands was a very dangerous business and many fatal accidents and drownings are recorded. The diary of William Fisher contains several examples of such melancholy events including February 29,1817, when ‘...a man was drowned…. in crossing Ulverston sands owing to the liting and storm.’

January 19, 1841: ‘...two young men... had been to invite some of there Friends … to the Odd Fellows Ball at the Kings Arms …. on there return home in the evening the wear lost upon the sand and when found next morning the horse and gig was stuck fast in the channel and one of the men entangled aboute the step of the gig the other was found a little below in some fishing nets the wear a long way below the foard.’

May 10, 1846: ‘a melancholy los of life 9 persons attempting to Cross the sands… got into what the call Black scare hole which is a hole 13 feet deep at low water the wear all in one cart every one with the horse Perrished it was supposed the wear the worse for licquor.’

Edwin Waugh, the Lancashire writer and poet, writing in 1869, described a terrifying experience crossing tidal channel,‘It is a wonder to me now how I got through that deep, strong, tidal current... My clothes began to grow heavy, and the powerful action of the tide swayed me about so much that I could hardly keep my feet.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe coming of the railways and improvements in road transport led to the virtual ending of the cross- sands route as a viable alternative and the coach and carrier services did not survive completion of the Ulverston-Carnforth-Lancaster rail line in 1857.

Since then crossing the sands has been mainly a recreational pursuit. The dredging of the Ribble and construction of training walls to allow large ships to reach the new dock basin at Preston made it impossible to ford the river at Freckleton, leaving only the new Shard bridge over the Wyre as the last remaining crossing on the old highway still in use as a public thoroughfare.